Water Sanitation Part 1: Biology of Pathogens in Water Sources

If you grow greenhouse crops, undoubtedly you have had issues with root disease pathogens. Often they come from any number of sources, one of which is water. This is especially true of water coming from a pond, river, lake or from a recirculated system. Well water and municipal water sources typically contain few pathogens. To protect crops, it is important not only to know where these pathogens are coming from but also to take the necessary steps to prevent pathogens from damaging crops. Sanitation is a key to restricting plant pathogen introduction and spread. In this first of a three-part series on water sanitation, we will discuss the importance of knowing the biology of root rot pathogens.

So where can pathogens be found in an irrigation system?

The largest source of pathogens comes from storage tanks or ponds where runoff water is collected after crops are irrigated. The problem is that growing medium and leaves from diseased plants contain pathogen fragments that flow into a holding tank or pond and “inoculate” these reservoirs. Another source where plant pathogens have been found is in biofilm, a complex of algae, bacteria and other microorganisms (including pathogens) that grow inside pipes, drip tubes or emitters. Capillary mats, sub-irrigation tables, flood floors and hydroponic systems that capture and recirculate water that comes in contact with diseased plants can then disseminate pathogen fragments to the rest of the crop. Other places where plant pathogens could be lurking include cracks and crevices in floors or benches, greenhouse walls, contaminated plants that are brought into the greenhouse, reused containers that were not properly cleaned, and worker clothing, shoes and tools.

Plant pathogens found in water sources

Not all pathogens will survive in water, nor will those that can, do so indefinitely. Viruses, such as tobacco mosaic virus, bacteria, such as Erwinia, Ralstonia and Xanthomonas, some nematodes, and fungi, such as Fusarium, Pythium and Phytophthora, have been found in “dirty” water sources. Of these, Fusarium, Pythium and Phytophthora are the most problematic root rot pathogens to be disseminated by water.

Pythium and Phytophthora

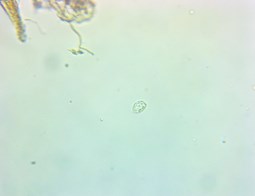

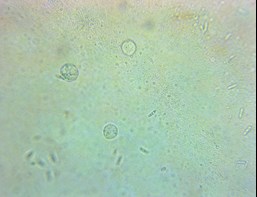

Pythium and Phytophthora are especially well adapted to spread through irrigation water as they both need water to complete their life cycle. Most strains of both pathogens produce swimming zoospores that are generated in high numbers in water. When zoospores come close to a plant root, they can easily find them through a process called chemotaxis and then infect a root.

Both fungi also produce survival spores called oospores that can live for months or longer in tissue and soil residues. These hearty structures can even survive without the presence of water. Often sanitizing agents are effective against zoospores, since they are weaker structures, but are less effective against oospores since they have thick walls and are often embedded in root fragments and soilless media. Sanitizing agents are often neutralized when coming in contact with organic matter, further making oospores difficult to kill.

Pythium is a very common pathogen that can be found almost anywhere in the native environment, so it is often the most common pathogen found in the greenhouse and also in water systems. Pythium tends to be a weak organism and is often easier to control than many other root rot pathogens. Phytophthora is a heartier fungus and fortunately is less commonly found in the natural environment and also in greenhouse crop culture.

Fusarium

Fusarium does not have a swimming spore stage, but spores and mycelial fragments can successfully travel in the water stream for short periods. Fusarium also produces spores that can survive for months without the presence of plant tissue or growing media. It too can be difficult to control with sanitizers, especially if its spores are embedded in root pieces and growing media.

Testing for Pathogens

If you believe that your water contains plant pathogens, have it tested by a lab to determine if and what pathogens are present. If the water is sanitized, it is good to have the water tested before being sanitized and also after sanitation to verify the sanitation system is working properly. Keep in mind that not all species of Pythium and Fusarium are pathogens. Some have been found to be beneficial to plants. Most labs have a difficult time determining the exact species of these pathogens, so if your water tests positive for Pythium, it may not be a pathogen. Even so, if Pythium levels drop significantly in a water source after sanitizing, this verifies that the water sanitation system is working.

In Part 2, we will focus on why cleaning the water is important before sanitizing the water.

For more information on this topic, please refer to cleanwater3.org or contact your Premier Tech Grower Services Representative.

Sources:

- Ratus Fischer. 2003. Troubled Waters? Grower Talks. April 2003, pg 53-55.

- Gary W. Moorman. 2000. Controlling Pathogens in Recirculated Water. GMPro. Feb 2000, pg 27-30.

- R. Wick, P. Fisher and P. Harmon. 2008. Biology of Waterborne Pathogens. GMPro 2008